In 1922, the tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered by the archaeologist Howard Carter. This was a major event in the history of taste and provoked a craze for Egyptian artefacts, which is sometimes known as ‘Egyptomania’ or ‘Tutmania’. The craze affected cinema, fashion, jewellery and architecture. In particular, the exquisite artefacts of Ancient Egypt were among the major influences on the Art Deco style of design. Art Deco was a glamorous, decadent style that flourished in the 1920s and 30s: it was the style of the Jazz Age. Art Deco emerged in France, but soon spread around the world, and became especially popular in America. It affected all forms of design, including architecture, interior design and fashion. The Art Deco style is instantly recognisable. It was based on angular forms like trapezoids and zigzags, as well as geometric shapes and sunbursts. Art Deco drew its imagery from a wide range of sources, both modern and historical. It was influenced by modern art, but also by the arts of Africa and Ancient Egypt.

France had been interested in Egyptian artefacts since the time of Napoleon, but the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb inspired French designers to incorporate Egyptian imagery into the new style. The solid gold funerary mask of Tutankhamun uses lustrous materials like gold and lapis lazuli, creating a sharp contrast of colour. It has sinister animal forms – the cobra and the vulture. Artefacts like this appealed on an imaginative level. They revived the romantic fascination with Ancient Egypt. This imagery was immediately incorporated into Art Deco design.

.jpg)

Of course, Ancient Egyptian artefacts were inherently luxurious because, by and large, the only examples that survived were things that had been buried in tombs, which had belonged to the elite of Egyptian society - Pharaohs, royal families and priests. This made them instantly compatible with the luxurious Art Deco style.

.jpg)

Cartier clock

This is a clock by Cartier (1927), based on the form of an Egyptian pylon or temple gate, specifically the Gate of Khons. It may seem absurd that this massive architectural form has been reduced down to a minute scale; there is no trace of historical accuracy, but it celebrates the imagery of ancient Egypt in an enjoyably naïve way. The surface is covered in hieroglyphics – the Egyptian system of writing – but none of them have been used correctly; they are treated purely as decorative motifs. In fact, two figures look like they are serving drinks. Of course, it is executed in the most expensive materials, including gold, mother-of-pearl, coral, lapis lazuli and emeralds.

.jpg)

Boucheron corsage ornament

This is a piece of jewellery by Boucheron, the great rivals of Cartier. This is a corsage ornament with lapis lazuli, coral, jade and onyx set in gold. This was designed for the 1925 exhibition. It is not such an explicit imitation of Egyptian forms, it is slightly more abstract, but the colours and motifs are clearly Egyptian in influence.

.jpg)

Claudette Colbert as Cleopatra

.jpg)

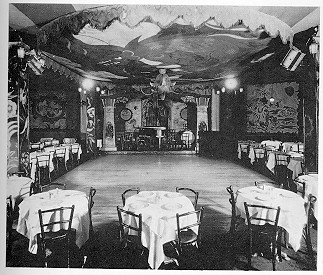

Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre

Hollywood was inspired by Ancient Egypt. The film director Cecil B. DeMille started to make historical epics like The Ten Commandments and Cleopatra, and constructed grandiose sets based on Egyptian temples and so on. These films also fed the interest in Ancient Egypt. But this imagery leaked off the screen and was used for the cinemas themselves. Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard was a famous example. This was designed in an overblown Egyptian style that summons up the mystery and glamour of a vanished age.

.jpg)

Cemetery gate, New Haven, Connecticut

The discovery of the tomb had other implications. This is an Egyptian style cemetery gate in New Haven, Connecticut. The Ancient Egyptians established a cult of death that was manifested in Tutankhamun’s tomb. This design revives that rather morbid association.

Perhaps the best example of American Art Deco is the Chrysler Building, built by the Chrysler Corporation and designed by William van Alen. The building is constructed from a steel frame. It is surmounted by a spectacular metallic spire that rises in a series of ascending curves based on sunbursts. The metal cladding was meant to resemble platinum. The ornamentation is based on car styling. The corners have these gleaming metallic eagles that look like modernistic gargoyles: they are replicas of 1929 Chrysler hood ornaments. Te building is a monument to the car industry. The lobby of the Chrysler Building is equally spectacular. It is entirely lined in amber-coloured marble with lustrous metallic fittings. This is an elevator door with a design based on the papyrus flower, another Egyptian motif. It is executed in inlaid wood and metal, making it very opulent.

.jpg)

For a discussion of Ancient Egyptian artefacts, see Lauren Axelrod’s excellent article:

http://factoidz.com/the-art-and-history-of-ancient-egyptian-jewelry/

-----

The largest archaeological find in history had become the best way to make money. First, the tomb benefited the locals in Luxor. The discovery helped transport owners, hotels, liveries and shopkeepers. One tradesman said to a reporter: "'Insh Allah [Please God], they find a new tomb next year also.'"(59) From there, the sensation spread like wildfire. In the same day that the Times reported that a New Yorker had bought the rights to filmed tomb scenes,(60) the newspaper also reported that Washington D.C.'s Patent office received a flood of applications for the use of Tut-Ankh-Amen as a trademark--objects chiefly for "women's use."(61) In fact, commercially, Tutankhamen made the biggest impact on women's fashion.  Egypt had been "advertised almost to the point of saturation," but the new interest manifested mostly with dress styles, according to one Art and Archaeology article.(62) "Printed materials sometimes of frightful vividness attempt to reproduce the scenery of Egypt with patterns of sphinxes, camels and palm trees. Dangling earrings and colored sandals help to complete the oriental picture."(63) For better or worse, Egyptian motifs had invaded America. "What was worn in the days of the Pharaoh was made to seem new," said another Art and Archaeology article.(64) The first signs that the fashion industry would pick up on the trend came as designers examined works at the Metropolitan Museum to glean ideas for designs.(65) |

Just days later the Egyptian influence exploded at the Hotel Savoy's design show by the Fashion Review of United Cloak and Suit Designers' Association of America. Designers used the show as a chance to remark on their superiority to European fashion: "'America is in a better mood to produce styles today than Europe'" because they are "'war mad.'"(66) One designer also said that the "Egyptian trend in clothes was on before the discovery of the tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen."(67) The Americans were determined not only to show their strength in the fashion world, but thought Tut-Ankh-Amen was the way to do it. Fashions, for the moment, shifted strongly toward Egyptian styles.  |

By February 26, 1923, H.R. Mallinson and Co., a silk firm, probably motivated by its own desire to expand, predicted that the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb would change furniture, decorations, jewelry and women's dress. Furthermore, the firm said that the tomb could possibly lead to a more extended revival--"a distinct epoch of Egyptian fashions, the adoption of flowing robes, a complete change in our jewelry, furniture and decorations."(68) The Chairman of the Dress Fabric Association, a silk group, said in July that the Egyptian fashions had created "through publicity an entirely new silk season…one of the liveliest the silk business has experienced in years." Yet alas, the chairman, F. B. Patton, dismissed the vision of a permanent Egyptian epoch envisioned by H.R. Mallinson and Co. (69)  The Egyptian fad, Patton said, was now a "thing of the past."(69)(Above left, a garment of coptic Egypt, fourth to sixth century A.D., Metropolitan Museum, New York. Right, an Egyptian feathered Head-dress and a gold diadem of a Princess. (April 1923, Art and Archaeology) The Egyptian fad, Patton said, was now a "thing of the past."(69)(Above left, a garment of coptic Egypt, fourth to sixth century A.D., Metropolitan Museum, New York. Right, an Egyptian feathered Head-dress and a gold diadem of a Princess. (April 1923, Art and Archaeology)

|

Others seemed to agree that Tutankhamen's time in the fashion world had come and gone like his short reign in Egypt, even before it was over. Art and Archeology's readers learned from the magazine that "fortunately for the true lover of art all this is but a passing fancy rather amusing while it lasts."(70) The National Geographic Magazine affirmed this opinion: "It is unlikely that the comparatively small tomb itself will have more than passing interest."(71) Still others deplored that the king was being used by entrepreneurs as a commercialized fad. Others seemed to agree that Tutankhamen's time in the fashion world had come and gone like his short reign in Egypt, even before it was over. Art and Archeology's readers learned from the magazine that "fortunately for the true lover of art all this is but a passing fancy rather amusing while it lasts."(70) The National Geographic Magazine affirmed this opinion: "It is unlikely that the comparatively small tomb itself will have more than passing interest."(71) Still others deplored that the king was being used by entrepreneurs as a commercialized fad.  "It is pathetic to think that the man who once ruled …is today but a mummy, a centre of acute interest…in a phrase, a 'new stunt.'"(72)Englishmen, in particular, for reason mentioned previously, were disgusted by the commercialism surrounding the find. "It is vulgar…for a man to aim do laboriously at carrying beyond the grave the magnificence of life. But it is at least as bad to exploit this old vulgarity of pride in the interests of the new vulgarity of commercialism."(73) "It is pathetic to think that the man who once ruled …is today but a mummy, a centre of acute interest…in a phrase, a 'new stunt.'"(72)Englishmen, in particular, for reason mentioned previously, were disgusted by the commercialism surrounding the find. "It is vulgar…for a man to aim do laboriously at carrying beyond the grave the magnificence of life. But it is at least as bad to exploit this old vulgarity of pride in the interests of the new vulgarity of commercialism."(73) |

|

Even as the New York Times reported the spread of the Egyptian motif in fashion, advertising copy in the 1920s shows how Tutankhamen influenced advertisers as well. In  a series of advertisements in the Saturday Evening Post, Palmolive compared their product to that of Cleopatra's own beauty products.(74) The ads featured scenes of a queen and a king in full regalia, waited on by servants and dressed richly. An ad in the New York Times, placed next to an article about Tutankhamen, showed the latest fashions--"The decorative splendors of the Tut-ankh-amen period are reflected in the rich embroidery motif on this distinguished Wrap-Over Coat with its aristocratic collar of bisque squirrel."(75) Yet at $95, only the most elite could feel like a queen for a day. Still, these kind of clothing ads offered everyday people the dream of being royalty in a time long gone. Still other ads testified to the longevity of Egypt. "Achievements that endure are the milestones along the great highway of progress," said a typewriter company's ad in the Saturday Evening Post that featured a picture of a typewriter beside a pyramid.(76) The message was longevity, which Americans identified with Egypt rather than their own civilization. a series of advertisements in the Saturday Evening Post, Palmolive compared their product to that of Cleopatra's own beauty products.(74) The ads featured scenes of a queen and a king in full regalia, waited on by servants and dressed richly. An ad in the New York Times, placed next to an article about Tutankhamen, showed the latest fashions--"The decorative splendors of the Tut-ankh-amen period are reflected in the rich embroidery motif on this distinguished Wrap-Over Coat with its aristocratic collar of bisque squirrel."(75) Yet at $95, only the most elite could feel like a queen for a day. Still, these kind of clothing ads offered everyday people the dream of being royalty in a time long gone. Still other ads testified to the longevity of Egypt. "Achievements that endure are the milestones along the great highway of progress," said a typewriter company's ad in the Saturday Evening Post that featured a picture of a typewriter beside a pyramid.(76) The message was longevity, which Americans identified with Egypt rather than their own civilization.  Full paper and footnotes. Related Article: Ancient Costume and Modern Fashion (1923) by Mary MacAlister. |

At left "Mrs. Asquith, wife of the British Prime ex-Premier, appeared in London recently wearing this gown draped in the manner popular when King Tut ruled." (Literary Digest, March 10, 1923.) Photo Sources: "At the Tomb of Tutankhamen." National Geographic Magazine XLIII: 5, May 1923: 467. (At left) McAlister, Mary. "Ancient Costume and Modern Fashion." Art and Archaeology 15, April 1923: 167-175. New York Times. 8 March 1923: 6.

New York Times. 25 Feb. 1923: 6.

New York Times. 9 March 1923: 5, 6.

New York Times. 27 March 1923: 7.

New York Times. 8 March 1923: 6. Uncovering Tutankhamen I The Boy King I Buried Treasure I Metropolitan |

-----

The Egyptian Ballet

Photograph by Putnam & Valentine, Los Angeles, reproduced from "Ted Shawn, Ruth St. Denis: Pioneer & Prophet, II" (San Francisco: Printed for John Howell by John Henry Nash, 1920): plate 2

-----

This Blog is fantastic! But if you want to watch any of the videos, scroll down to the bottom and pause the ambient music first.

Fascination With Egypt

-----

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)